Mosaics in the Roman World

Most mosaics were laid on the floor. They form one of the most well-preserved and widespread types of Roman art, found throughout the Roman Empire from Britain and Spain in the west to Jordan and northern Mesopotamia in the east. They were used in public buildings such as Roman baths and marketplaces and, in late antiquity, in places of worship such as synagogues and churches. The majority of mosaics however decorated private buildings, both large city houses and villas in the countryside or by the sea. Mosaics were a costly and time-consuming addition to a property, although they would thereafter require little maintenance and could be expected to last a lifetime. Because of the heavy initial investment however considerable care and attention was paid to create designs that were attractive and appropriate, both to the owner and to the setting.

Mythological scenes were popular, presumably because they were timeless and familiar classics, though they may also have been deliberately chosen to signify the owner’s learning, taste, and sophistication. Scenes of what may be called daily life, activities such as hunting, fishing, circus races and games involving gladiators, other fighters or animals, also had great appeal. Some of these are subject specific, depicting, for example, the lord of the manor and his retinue or contestants in the arena complete with their names. Perhaps the most famous example however is the mosaic in the entrance to the House of the Tragic Poet at Pompeii in which a ferocious-looking guard dog is depicted together with the warning cave canem (‘beware of the dog’).

Despite all the diversity in their manner of execution, design, geographical setting, and dating, Roman mosaics display a number of shared or common characteristics. So it is likely that some elements of the Lod Mosaic drew on standard pattern books, perhaps even ones compiled elsewhere in the Roman Empire. Parallels for some features of the Lod Mosaic can be found on other examples from the same region, but North African mosaics have also been regarded as the source for some of its elements. Similar patterns and scenes however can be seen on mosaics throughout the Roman world. For example, counterpoised dolphins are common on Hellenistic mosaics from Delos, marine scenes figure on mosaics recovered from Pompeii, and panels depicting animals and birds within geometric frames appear on floors at Cologne in Roman Germany.

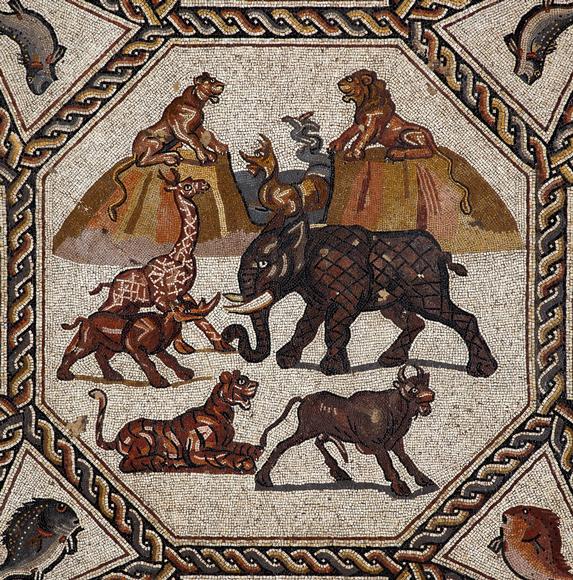

The depiction on the Lod Mosaic of solitary or paired groups of creatures, such a large feline hunting a grazing animal, forms part of the common stock of genre subjects. Nevertheless, the composition reveals essential differences to other known mosaics, implying that the choice of subjects was deliberate and specific. For example, the central panel with the assortment of African and other animals defies immediate interpretation. The foreground echoes scenes of the amphitheatre where exotic animals were presented in the arena as part of public games put on either by the emperor or by a local patron of high standing. Certainly the depiction of an elephant, giraffe, and rhinoceros would have been very striking in a place such as the Roman colony of Lydda on the coastal plains of ancient Palestine, where such animals would have been unfamiliar. The addition in the background of two rocky outcrops, interpreted as the mountains of Ethiopia, implies a natural setting for the animals. However, they flank an expanse of water in which a mythical sea creature known as a ketos is depicted. This may represent the Ocean that was believed to encircle the ancient world and, if so, would reinforce the idea of distant lands and creatures. It is possible that such a subject was of particular significance for the patron who commissioned the Lod Mosaic. It is certain however that he was a wealthy local resident who wished to have his home decorated in the finest Roman style.